Literary Monster Descriptions

And so, the NatheQuest bestiary continues.

Something I've been thinking about is appropriate descriptions for monsters, particularly in terms of appearance. There are two main issues I've noticed in bestiaries. The monsters rely on artwork, text description, or player presuppositions. The latter is okay in some cases. We know what a Viper looks like, so it doesn't necessarily need that much description; an Orc is different. I don't know what an Orc is in a concrete sense. Given the way RPGs come alive at the table, I think there is a strong argument to made that games should avoid using artwork as a crutch. The imagination of players at the table ought to be inflamed by the text and the dreams they inspire, more than the art.

The other issue is disharmony between the mechanics and the physical description of the monster. That is: the cause and effect is unclear. When running a challenge oriented style of game, as I do, its important that the monster description indicates the monster capability. I tend toward transparency, anyway, but unity between text and mechanics makes the game feel smoother at the table.

My solution to these perceived problems is what I think of as Literary Monster descriptions. That means a few things. First, assume there is no artwork to be paired with the text. If artwork is to be used, an artist ought to make an illustration afterward based on the description. Resist the urge to simply describe a cool design you've seen: the monster should come alive in your head before hitting the page. Second, assume minimal foreknowledge on the part of the reader. If you were writing a book, how would you describe the monster? While the goals of RPGs and stories differ, it makes sense to turn to literature given that RPG content is recorded with text. Third, the monster should matter and be able to generate play. One off creatures that you fight and move on from have a place, but for Monsters I prefer them to be more significant. Finally, I mean Literary in the sense that the text should be evoke feelings and inspire the passion of the reader.

I will provide some examples from my NatheQuest bestiary. I am by no means claiming this is the best approach, or that my monsters are something amazing. I'd just rather use my own work than someone else's for most of my examples.

For a good case study of different approaches to a Monster Manual, compare OD&D with Luke Gearing's Monsters &, and Skerples' Monster Overhaul. All three of these have vastly different approaches, broadly in the style of Wargame Minimalism, Poetic, and Comprehensive respectively. Each has pros and cons and are interesting in their own right.

-

Here is a rather innocuous example of a poorly done monster. The 5e Orc is basically fine. However, its design lacks a certain clarity of design that makes it difficult to really express purely in text. The 5e description is such: "Orcs are burly raiders with prominent lower canines that resemble tusks. They gather in tribes that satisfy their bloodlust by slaying any humanoids that stand against them." Without the visual, I would simply imagine a man with tusks. That's actually a fine thing to imagine. It is more interesting than the Generic Fantasy Looking Orc Dude below, but it's still completely lacking in interest. My attempt to upgrade the description: "Its arms hang past its knees, and its ears look too small for its massive head. Tusks jut out in place of their lower canines. A man twisted by war until it is a man no longer."

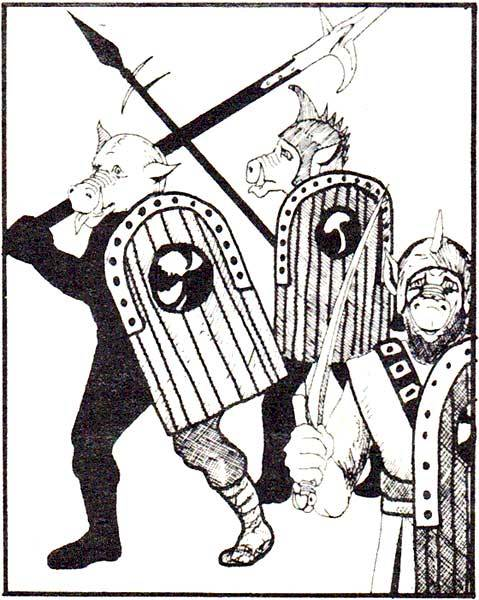

An alternative Orc design:

These guys can be physically described as follows: "Boar headed men." This is imminently imaginable, and has Classical connotations: Herodotus wrote of rumors Cynocepheli (dog headed men) and all other manner of humanoid monster (This history, and the revival of such images in the Early Modern Period, is problematic and interesting but not altogether relevant for this blog post). The crux of the monster can be communicated in a single sentence: there's less "slippage" between the artwork and the description of the appearance. If you are only using text to communicate your monsters, as I think is best, then monsters should be pared down into base elements. Those elements should relate to things that readers can grasp quickly and easily.

With such a simple physical appearance, the rest of the description can do more work. NatheQuest Orcs are described as such:

Orc

1+1HD 7AC As Weapon 30'

-

Boar headed man. All tusk and sinew. Orc bands menace the mountains and deserts, and are enemies of the woods. They wage a perpetual war; their homes are makeshift camps and forts of rough hewn stone. Orcs are cursed: the land they live on inevitable withers away.

-

This description provides some adventure hooks and bits of history that will aid me when I fill out the NatheQuest hex crawl. It also provides a conundrum: what is the ethical solution for dealing with marauders that have literally no choice but to be mauraders? With the incoming climate apocalypse, which will certainly force desperate peoples to warfare and conflict as much of the world becomes increasingly unliveable due to draught and rising water, I think this is genuinely an interesting issue. That's a Literary Monster: something that has a simple, evocative description and actual thought/feeling put into its role within the campaign.

5e's monsters are problematic because monsters are mainly described by stat block. Orcs are Aggressive, and this is defined mechanically. The stat block states that "As a bonus action, the orc can move up to its speed toward a hostile creature that it can see." This does nothing to inspire or excite. I am not sure how the 5e Orc is supposed to function on a thematic level.

The Dragon is a classic monster. Sheep & Sorcery posted an excellent blog post about the issues with the typical paradigm of RPG dragons. To avoid bullying 5e, I dug up a statblock from Fabula Ultima. Here you see an issue described in Sheep & Sorcery's post: "having one dragon being very different from another is great. Having a bunch of breeds and species of dragons turns them into regular animals."

The description states that there are numerous types of Dragons and, given that it is roughly the same strength as a Mercenary it is clear that this is a Naturalized depiction of a Dragon. Rather than taking the role of a mythological beast, it is an animal like a cow or a person. The Drake is prosaic.

For contrast, here is an attempt at a Literary Dragon:

Dragon

8HD 1AC 2d6 40'/80' (Flight)

-

The king of monsters. It's opalescent scales are harder than the strongest panoply, and its sword-talons rend flesh with ease. The heat of its body is unbearable; smoke billows out of its orifices. Its man-sized fangs cleave through the symbolic order and establish the Dragon as beyond reason. Above all else Dragons covet treasure and beauty and destruction.

Men who look into the cat eyes of a dragon become victims of possession. They become irrational servants of the dragon, bequeathing gold and daughters upon it, or perhaps they lose their sanity completely.

Each round, the Dragon may attack with its claws, tail, and either its head or wings.

Claws: The Dragon may perform sweep attacks like a Fighter with its claws. Sweep attacks are applicable on targets the size of a bear or smaller.

Tail: While most fear the Dragon's breath, its tail is its most deadly weapon. It is incredibly articulate and strong. Each round the dragon will either launch a tail strike behind it, knocking foes back 20' on a failed save, or it will attempt to coil around and grab an opponent. A grabbed opponent will either be thrown next turn, or they will be constricted to death.

Head: The head may bite for 3d6 damage. Alternatively, the Dragon may blast a vent of flames (90'x30'). This deals 3d6 damage to all in range. It must use a Head action to recharge its flames.

Wings: With hard flaps, all figures in the area must save or be knocked prone. It will often flap its wings before ravaging enemies with its sweeping claws.

-

The Dragon here is inspired in its physical descriptions by Tales of Earthsea and the concept of the Dragon as a sort of incarnation of, as Traverse Fantasy calls it, D&D's Obsession With Phallic Desire. The Dragon makes an obvious phallic image, and is already associate with greed. As Marcia writes, the phallic drive "is the impulse to constantly seek out objects which seem to have the ability to fulfill one's desire; in other words, the phallic drive is desire itself." That's why I chose to have this Dragon mute. It is desire itself. No words are needed. This is also why its possession only affects men. The Dragon is included by some aspiration beyond the obligation to include a Dragon in my elfgame.

Mechanical complexity does not require massive statblocks, and involved fights are something I'm quite fond of. I have grown to prefer prose descriptions of monster attack routines that, unless necessary, avoid using mechanical language to describe the effects. In NatheQuest there are various effects here you can make a Save against such as possession, fire breath, and wing flaps. Rather than state this explicitly, I leave it up to the discretion of the play group to determine where a save is reasonable.

Rules can be broken. While simple appearances are great for creating a clear vision at the table, there is a place for incomprehensible monsters. Lovecraft or the "biblically accurate angels" that people meme about are great examples. In the following Monsters & entry, Luke Gearing creates an impression of something so vast it cannot be properly conceived of (This is one of my favourites from the book):

Writing my monster entries "text first" and with thematic interest has produced content that I am very interested in playing with and running. The core of the Literary Monster is really to just try trying with your monster entries. Give things time, let ideas cook, and don't phone it in. Do not include a monster just because it seems to be a given: make sure the idea has meat. You can go very far with humans and animals alone: monsters must be special to justify their existence.

Comments

Post a Comment